Richard Henry Polglase

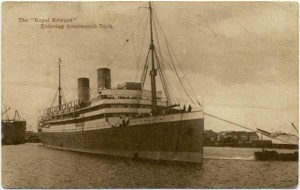

RICHARD HENRY POLGLASE & HM TROOPSHIP `ROYAL EDWARD`

By Kathryn ATKIN (nee Polglase).

My Grandfather Richard Henry POLGLASE was killed with about 60 other Cornish volunteers when the troopship ROYAL EDWARD was torpedoed in the Aegean Sea 13 Aug. 1915. There were about 100 Cornishmen in the 18th Labour Coy. A.S.C.

Four volunteers were from Helston, but apart from my grandfather I have found out the name of only one – Richard Joseph JAMES. It is easier to find the name of those who died. There is also Alfred Ernest SMITH from Helston, but he was born in Epsom, Surrey.

R. H. Polglase lived 33 Wendron St. and R. J. James was son of Peter James, 1 Godolphin Rd. -his wife Alice Maud lived 84 Park Road, Camborne when she sent information to Commonwealth War Graves Commission (C.W.G.C.)

BRITISH TROOP SHIP SUNK

———-

TORPEDO ATTACK IN AEGEAN

———-

600 SURVIVORS

———-

FEARED LOSS OF 1,000 LIVES

The Secretary of the Admiralty announced yesterday that the transport Royal Edward had been sunk by an enemy submarine in the Aegean Sea. The loss of life was apparently about 1,000, those on board numbering just over 1,600 and about 600 being saved. The following is the text of the Admiralty announcement:- The British transport Royal Edward was sunk by an enemy submarine in the Aegean Sea last Saturday morning. According to the information at present available the transport had on board 32 military officers and 1,350 troops, in addition to the ship’s crew of 220 officers and men. The troops consisted mainly of reinforcements for the 29th Division and details of the Royal Army Medical Corps. Full information has not yet been received, but it is known that about 600 have been saved.

THE SHIP AND HER RECORD.

The Royal Edward was built on the Clyde in 1908. She was a steel triple-screw steamer of 11,117 tons, with a length of 545ft., a breadth of 60ft., and a depth of 38ft. With her sister ship, the Royal George, she was originally constructed for the Egyptian Mail Steamship Company’s service between Marseilles and Alexandria, the names of the vessels being then respectively the Cairo and the Heliopolis. After one season’s running the two steamers were acquired by Canadian Northern Steamships (Limited), and underwent certain alterations. The topmost deck of each boat was taken off, and the hull greatly strengthened for Atlantic weather. The vessels were employed for the mail service between Avonmouth and Montreal. The liners were luxuriously furnished, and equipped with all the conveniences of the modern floating hotel. Communication between the four passenger decks, to mention only one feature, was provided by electric lift. Both ships were fitted with wireless and submarine signalling apparatus. The captain of the Royal Edward was Commander P. M. Wotton, R.N.E. After the war broke out the Royal Edward was one of the many fast merchantmen requisitioned by the Government. She assisted in bringing the Canadian contingent to England. Later she was used for interned enemy aliens for several months, and latterly as a troopship. When on the Atlantic service she carried many distinguished English and Canadian statesmen to and fro, including Earl Grey, Governor-General of Canada, and Sir Robert Borden now the Canadian Premier. A large traffic was done with emigrants, the West of England being the favourite area for Canadian emigration agents before the war. The majority of the officers and crew belonged to Bristol, and distressing scenes were witnessed at the Bristol offices, where, however, there was little information available.

———-

STATIONED OFF SOUTHEND

———-

ROYAL EDWARD AS INTERNMENT SHIP.

When Mr. John B. Jackson, of the American Embassy in Berlin, visited this country to report on the treatment of German prisoners of war in England, he inspected the Royal Edward, which was then being used as an internment vessel. In his report he stated as follows:- Of the ships, the Royal Edward was obviously the show ship. On board, the interned were separated into three classes dependent to a certain extent upon their social standing, but to a greater extent to their ability to meet extra expenses. prisoners were permitted to avail themselves of the regular first-class cabins upon payment in advance of from 5s. to 2s. 6d. a week, according to the number of persons occupying a cabin. At that time the ship was lying off Southend, and Mr. Jackson reported that all the prisoners were locked below decks at night, which caused some nervousness among them owing to the apprehension of danger from Zeppelins.

———-

THE LOST TRANSPORT

———-

FIRST ENEMY SUCCESS OF THE KIND.

Our Navy Correspondent writes:-

After a year’s work which has been in all respects brilliantly successful, and for which no praise can be too high, the British Transport Service has had the misfortune to lose one of its finest vessels in a torpedo attack. There is something peculiarly distressing in the circumstances in which a thousand gallant souls are missing without an opportunity to strike a blow for their own safety or defence, and the ready sympathy of the nation will go out to the relatives and friends of those who have perished. At the same time, all who grasp the magnitude of our transport operations may well marvel that we have hitherto been spared such a disaster. That this first loss of a British transport should have occurred in connexion with the operations at the Dardanelles is significant. The convoy of large bodies of troops through the Mediterranean, where not only German but Austrian submarines are known to be operating, must throw upon the Navy very heavy responsibilities. These are not lessened, moreover, by the fact that, as we have been told officially, only our surplus ships and vessels are being used in that theatre of war. This misfortune will serve to bring home to the country as nothing else could the marvellous work which has been done by the Navy and Mercantile Marine in conjunction in ensuring safe transport for the troops not only between these shores and the Continent, but to the Aegean, and from all our Dominions across the oceans. The last-named task was satisfactorily performed at a time when the German raiders were still at large, and it will be remembered that the Sydney was actually convoying an Australian contingent across the Indian Ocean when she received by wireless news of the arrival at Cocos Island of the Emden. Mr. Churchill said that approximately 1,000,000 men had been moved without any accident or loss of life. That was six months ago, and the number must have been doubled in the interval. The only occurrence modifying the late First Lord’s remarks was the attempted torpedoing of the transport Manitou in the Aegean on April 17. The Turkish torpedo-boat Dhair Hissar escaped from Smyrna, stopped the vessel and ordered the troops to abandon her. Two torpedoes were fired, but missed and the torpedo-boat was then driven off and run ashore by British destroyers which had come up, the crew being captured. Owing to two boats being upset in leaving the transport 51 lives were lost. For a parallel case to the loss of the Royal Edward it is necessary to go back for over 20 years to the sinking of the Kowshing during the Chino-Japanese War. This vessel, which had left Taku with 1,200 Chinese troops and guns, as well as small arms and ammunition, on board, was sunk of Chomulpo by the Japanese cruiser Naniwa. Whether the ship was sunk by torpedo or gun-fire is in doubt, but about a thousand of the Chinese soldiers were drowned. An idea of the magnitude of the Transport Service is afforded by Mr. Churchill’s statement that the Admiralty have on charter approximately one-fifth of the total British mercantile tonnage, or about 4,000,000 tons. It is pertinent to recall that while this task of transportation has been carried out under the protection of the Grand Fleet in the North Sea, and has been conducted by naval convoys, it is the Mercantile Marine upon which has devolved the actual business of the undertaking. Hitherto, beyond the public acknowledgement which Mr. Churchill made in February in the House of Commons, no official recognition has been made of the great service which has been rendered in connexion with the progress of the war.

THE TIMES

Tue. Sep. 7, 1915, p.5

MEMORIAL AT SEA ———- SERVICE WHERE THE ROYAL EDWARD SANK ———-

We have received from the Rev. Basil K. Bond, Chaplain to the Forces, who is attached to the hospital ship Devanha, an account of one of the most impressive funeral services of the war. Three weeks ago the country was told of the sinking of the transport Royal Edward in the Aegean Sea, with a thousand of the men she carried. Even before the news of the disaster was published here, a memorial service was held over the spot where the ship went down, and the bodies of those who had lost their lives were solemnly committed to the keeping of the sea. “It is our hope,” writes the chaplain, “that the thought that such a service was held may give some comfort to the bereaved at home.” The Royal Edward was sunk a few minutes after 9 o’clock on the morning of Friday, August 13. The news quickly reached Alexandria, where the hospital ship Devanha was getting ready to sail, and at the suggestion of the captain it was arranged that a memorial service should be held at the scene of the disaster. The Devanha left Alexandria, and on the following evening those on board knew that they were nearing the spot for lifeboats, lifebelts, soldiers’ water bottles, planks, and other pieces of wreckage were seen floating on the water. Soon after half-past 8 they came close upon the place, and the ship’s bell tolled slowly while the Europeans in the ship assembled on the boatdeck to pay the last tribute to the dead. All were there – the captain, officers, engineers and stewards, the doctors, nurses, orderlies, and some of the men of the Royal Army Medical Corps who were passengers. The service began with the hymn “Let Saints on earth in concert sing.” Then came the opening sentences of the Burial Service, followed by the 46th Psalm – “God is our help and strength.” During the singing of the Psalm the vessel slowed down until it stopped right over the place where the Royal Edward lay. The lesson was read, and the committal prayer for those buried at sea followed. The collect for All Saints Day, the prayer for those in anxiety and sorrow, and the prayer for our soldiers and sailors were offered. Then, as the ship gradually proceeded on her way, the blessing was given, and the hymn “Now the labourer’s task is o’er” was sung. The National Anthem and the Dead March in Saul brought the service to an end.