Street ‘Kennels’

Since a young age I have been fascinated by the small channels of water running down either side of the streets in Helston.

Known as `Kennels` rumor has it that they were originally located in the middle of the street and used by the local inhabitants to take waste away from shops and houses.

They also provided `relatively` clean water for washing down the road and pavements.

Probably originally no more than a dirt channel in the street they have, over time, been developed into a sophisticated system of granite water courses.

Kathryn Atkin recently wrote to me with an excellent `snippet` of information about the Kennels from the early 1900`s:

“My dad said he and other boys would float a stick tied to a piece of string down a kennel, jiggle it and an old man would go for it with his stick, thinking it was a rat.”

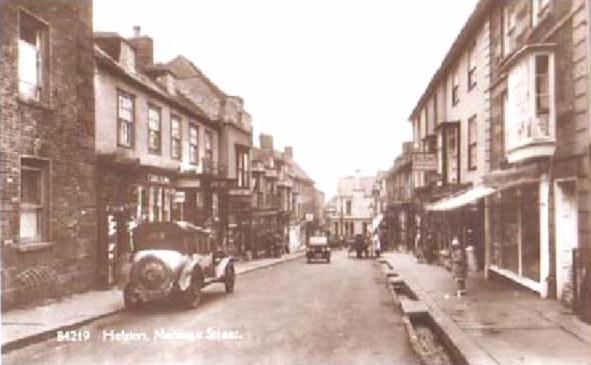

Unfortunately, over the last decade several of the kennels have been covered over, namely in Meneage Street, preventing the unwary car driver or pedestrian from inadvertently dropping into them. Having witnessed the spectacle several times, once a driver has got his car wheel into the Kennel it is extremely difficult to get it back out!

The kennel is still there but has now been covered.

So, the question that has always intrigued me and probably anyone who has actually visited Helston is `Where does the water come from`?

Recently I joined my father Fred Matthews and friend Raymond Lewry in the Cober Valley just below Wendron Church to locate the main water source.

Located in the River Cober is a small `Weir` which dams the water back giving a working `head` of water to be taken off into the Kennel system.

To enable the water authority to control the amount of water taken off the Cober and in times of engineering work shut off the supply completely, a sluice gate is located in the `leat` off from the weir. By raising/lowering the gate the amount of water entering the system can be easily controlled.

However, in certain circumstances, perhaps when there has been an unexpected storm causing the amount of water in the River Cober to increase dramatically, there is a fail safe system to ensure that the kennel system does not overflow. If the flow were unchecked the system would overflow with possible flooding or engineering damage in the town.

Therefore, just as in a full scale canal system an overflow has been constructed immediately below the sluice gate. During normal flow the water level in the system is not a problem, but if the water level rises rapidly the `spillway` allows the excess to return back to the River Cober. There is even a grill as an extra safety feature to prevent the pipe from becoming blocked.

From then on its downhill all the way to the streets of Helston.

Once it gets to the Water-ma-Trout area of the town it further divides to supply the various streets.

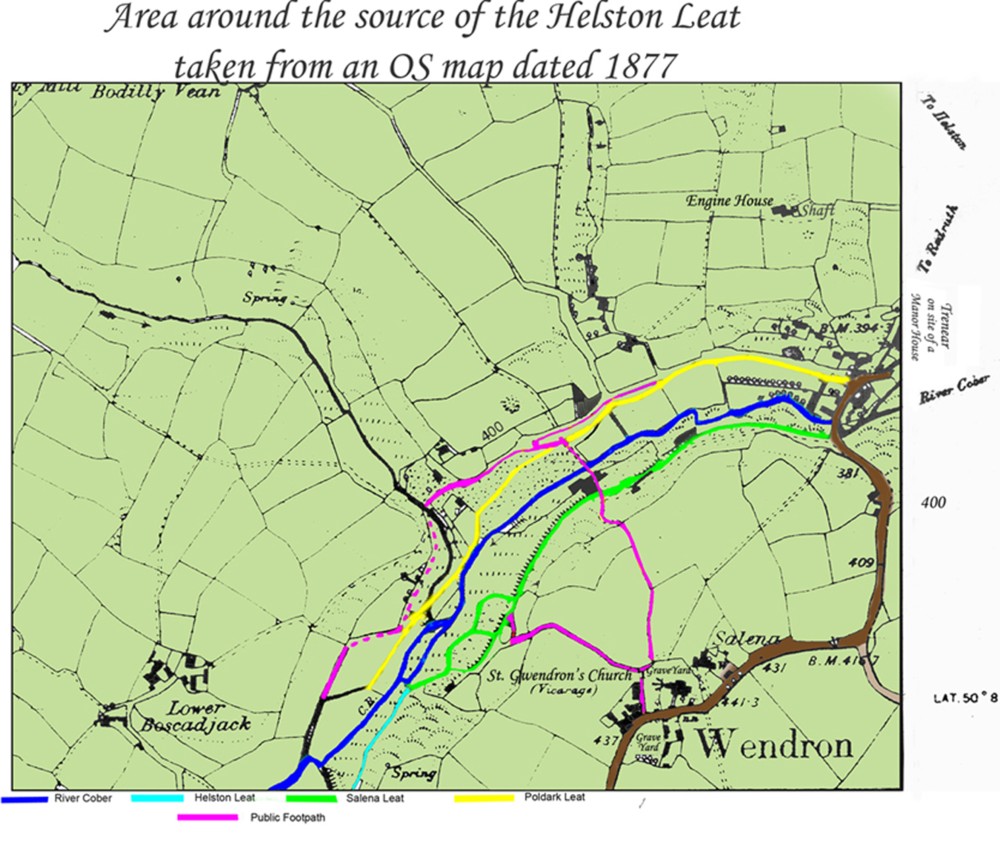

The map shows the River Cober, Helston Leat, Salena Leat & Poldark Leat around the Wendron area.

THE LEATS OF HELSTON

JOHN LAWSON

on CORNISH KENNELS

Two experienced pairs of eyes studied the situation closely.

`Do `ee reckon he`s gawna get out?

`Ais, if `ee drives down a bit.`

`Naw, you`re fergitten the deep `ole by the Blue Anchor.`

`ah, well, they lads in the furniture shop `ave a job then.`

The occupants of a public shelter at the bottom of Coinagehall Street, Helston, Cornwall are in what can only be described as an umpire`s position as they assess the chances of a luckless holiday visitor who has just parked his car in the street. His nearside wheels have just slid gently into the kennel where the tyres are being washed by the stream of water and he has two options. He can try driving down the kennel, other vehicles permitting, and with luck wrench his car onto the roadway, or he can seek help which is usually readily forthcoming.

The above imaginary dialogue from the two observers of a much repeated scene could be typical of an ordinary summer`s day in Helston.

The local district councils deserve commendation for preserving these kennels or leats and ensuring that the water supply is maintained. The hapless visitor may curse them but they are a remarkable feature of this Cornish country town.

The actual street kennels are about a foot wide and six to nine inches deep. They are mostly edged with granite blocks and the bottom seems to be cobble stones. There is usually three to four inches of water burbling along them. They are situated between the pavement and the road and, incidentally, their water flow removes some of the street debris.

Other Cornish towns have these kennels but none so far as I know has such a comprehensive system as Helston. Enquiries to Helston Museum (a delightful place to visit) and other local figures interested in the history of the town reveals little as to when they were constructed. Estimates are vague and range from late medieval to early Victorian times. The museum, I understand, has access to a document in the latter period referring to stones for the kennels but the quantity is so small that it may only have been for repairs.

Then we are left with the intriguing question of why they were made? Again opinions differ and I can only offer four suggestions gleaned locally:

a late medieval drinking water supply;

to supplement the town`s spring in Fivewells Lane and provide water for washing and domestic use;

to wash tin ore;

to supply the castle moat.

A castle once stood at the foot of Coinagehall Street where the present day bowling green is sited (one of the oldest in England) behind the Victorian Grylls Arch. Henliston Castle as recorded in the Domesday Book was once owned by Robert, Earl of Cornwall, half-brother to the Conqueror himself. The suggestion is that the leats were made to maintain water in the moat on the east side of the castle or where the Grylls arch now stands. There was a further idea concerning driving water mills but the water volume is rather small.

Examining the theories – all of which have merit – I am of the opinion that I cannot discount any of them.

It is usually accepted that early Norman castles were of the Motte and Bailey type and made of wood. Short moats to give extra protection to the sides that did not have natural cliffs (Henliston Castle had cliffs or steeply falling ground on three sides) were quite common.

The only difficulty with this concept is that the leats also run in Cross Street and Church Street and this area inhabited in ancient times is below the castle`s eminence and would have offered no benefit to the castle.

Helston from early times, probably before it received (or possible bought) its Royal Charter in 1201, was a tin trading town, hence the theory about the kennels being used to wash tin ore. After 1066 the language of the Court and to some extent the language of business was Norman French. Latin was reserved for religious and legal purposes. In order to test an ingot of tin the assayer chipped off a corner from the ingot – `un coin.` If the assaying was carried out in premises in that street, the name Coinagehall street is derived.

The practice of processing ore close to a harbour continued into the 18th century and helston had a harbour up to the 13th century until storms and tides closed the bar and created the lake now called Loe Pool. It may surprise locals to know that the present River Cober may have been tidal as far as Lowertown.

The theory of tin ore washing is of value but again the other leats previously mentioned detract from it.

The first two suggestions deserve more consideration and my own view is a combination of both. A 12th century town with its tin trading and market for the surrounding farms grew sufficiently to need more water supplies. In later years the system was gradually enlarged until the original water supply could not cope. My guess is that someone devised the present arrangement in the Georgian period. Whoever it was, I have considerable respect for them as the work entailed a major feat of water engineering. The surveying required to transfer water from one valley to another without pumps needs to be of a very high order.

The River Cober was dammed about two miles from Helston to start the leat. The dam can be found in the valley behind the New Inn at Wendron on the Redruth Road out of Helston. Access to the river is almost impossible in wintertime despite the public footpath as the depth of mud in the field adjacent to the river is horrendous. It came over the top of my wellingtons and I was stuck for ten minutes.The leat then runs down the Cober Valley and it can easily be seen at the bridge over the Cober leading to Coverack Bridges. At this point the leat is about three feet above the level of the river and a new spillway ensures that the water flow is not excessive.

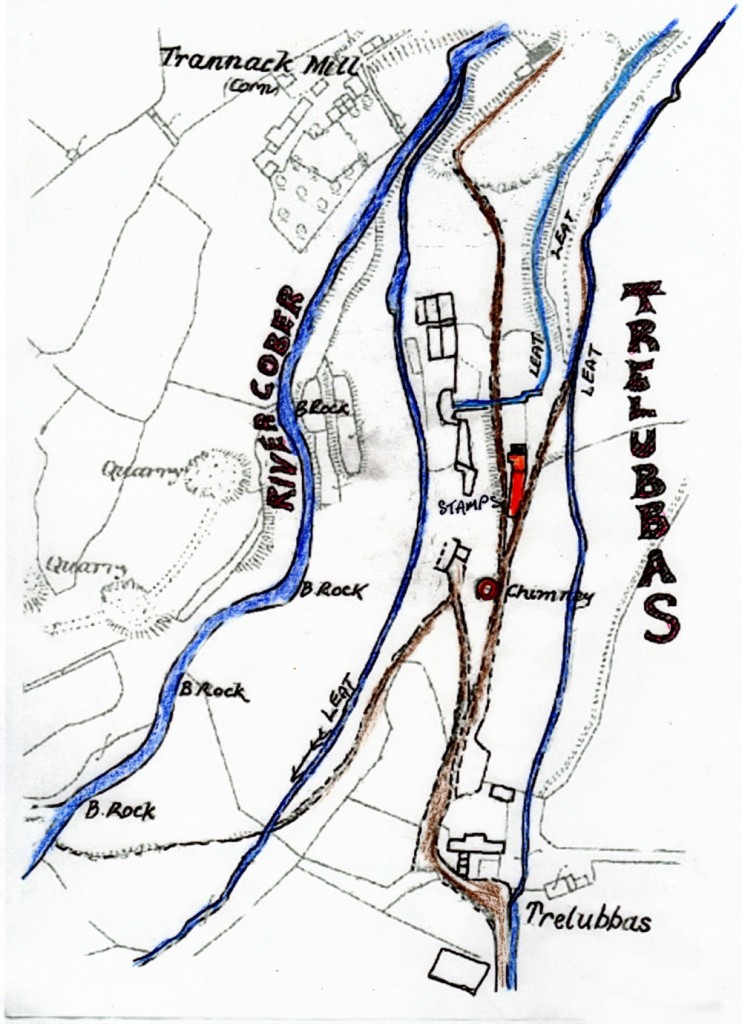

The next section is the most dramatic. This is where very careful contour following was required because the leat had to leave the Cober valley and cross to the line of the Redruth Road into Helston. To do this the leat runs high up the side of Rocky Valley (a local name), along the top edge of a disused quarry and then through the farm at Trelubbas Wartha. Here is flows beside the farm entry road and then disappears into a field just where the farm road meets the old route of the Redruth Road.

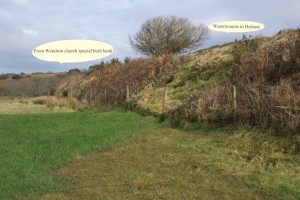

It is the route of the leat along the top edge of a quarry that inclines me to the opinion that this is a 19th century construction. The leat now continues in a modern pipeline but folowing the original route under the Lowertown Road and then most amusingly along the top of a Cornish hedge. I have to admit that before the present pipe system eas installed it was the sight of an open leat flowing along the top of a Cornish `hedge` which caught my interest. The pipeline, although it detracts from the original charm of the open leat, must have been necessary to reduce maintainance costs.

For the uninitiated, a Cornish hedge is a fearsome edifice. It comprises a mound of earth and stones about five feet wide at its base and tapering to about two feet at the top. The height can be from three feet to over six feet and there are considerable variations. The sides of this compacted mound are dressed with stones and eventually the whole hedge becomes overgrown with grass, blackberries and hawthorn. It looks innocuous but it is an impenetrable barrier. As a further digression one can find similar hedges in Normandy – this is the dreaded `bocage` country which gave the Allied tanks so much trouble in the Second World War.

Visitors to Cornwall should be warned that Cornish Hedges in narrow lanes have the disconcerting habit of moving into the path of unwary motorists and the stones then take their toll of the paintwork or worse.

At a modern industrial estate called Water-ma-Trout (Does anyone know the derivation of this name?) the leat divides. In the 1960`s this was a control point as the water in the leat could be switched to flow towards St. Micahels (Helston`s Parish Church) or towards the turnpike at the top of Godolphin Road where the tollhouse used to stand (removed in 1938). I do not know if the facility still exists.

The right hand branch towards the church can be best seen where it tumbles down beside the churchyard wall, past the old school and down the opposite side of Church Street.

The other route is more complex but after crossing a housing estate and going underground it emerges near the top of Godolphin Road.

It is almost a straight run down the left hand side of Godolphin Road to the junction of Wendron Street with Penrose Road where it divides again. The tributary which trickles down Penrose Road past the old Grammar School where Charles Kingsley (of Water Babies fame) attended then flows into Church Street to meet the water from the opposite direction. These leats combine, flow under the street and then flow behind the garden of Lismore House, under the road of Nettles Hill and then back into the River Cober.

The main leat down Wendron Street goes into a pipe again and under the road in front of the Town Hall where (I think) it divides to flow down each side of Coinagehall Street to entrap the unwary and provide a distictive aura to one of the broadest of Cornish Streets.

Photographs of Meneage Street, the other main street of Helston, taken before the First World War show that it had double leats. Regretfully these are now gone.

THE COUNTRYMAN

THE KENNEL’S WATERCOURSE

by CARLA EDDY

According to W F Ivey, at one stage there were 32 waterwheels fed by man made watercourses with the water of the River Cober.

The 1201 King John Charter was all about industry permitting tin investors to divert the water into man made watercourses (then wooden launders) of the Cober without asking each time the king.

At Coverack Bridges there was a tin stamps waterwheel and this was fed by the water from the River Cober via a man made watercourse which is also the feed to the Kennels in Coinagehall street. The sluice gate is behind Wendron church.

COVERACK BRIDGES STAMPS IN THE 1920’S

On the extreme right is TOM JOHNS, a native of Breage, who managed the stamps assisted by his son THOMAS WILLIAM JOHNS and the two others (names unknown).

This view is full of facinating detail.

On the far left an unusually broad water wheel drives a set of stamps, rag frames are in the foreground and at the rear of the shed on the right is a round frame.

Tom JOHNS is working a KIEVE.

On the skyline is the WHEAL DREAM ENGINE HOUSE & STACK, pasr of TRUMPET CONSOLS demolished in the 1940’s

(photo ERIC EDMONDS)

The raised cornish hedge double with watercourse on top.

At Franchis Farm, the leat is located just upstream from the place at Coverack Bridges where there was the original tin stamps.

Wooden launders carried the water closer to the waterwheels.

When I discovered the Charter by King John gave tinners the right to divert water from the Cober to process tin, I then went on to find that the kennels in Helston are because of the tin stamp connection.

A reference in Wendron church to the monks of Rewley Abbey suggests that they may have been the original constructors of the watercourses.

These monks had the monetary appropriation of Wendron which could have been used for payment for the work done.

Carla V Eddy

of

Trelubbas Wartha

Wendron